SHauKeeN GaBRu

Chardi Kala

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td><td width="10"></td></tr></tbody></table>Who divided India?

</td><td width="10"></td></tr></tbody></table>Who divided India?

November 29, 2006

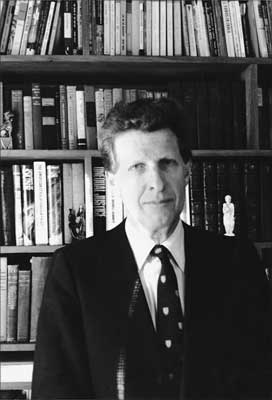

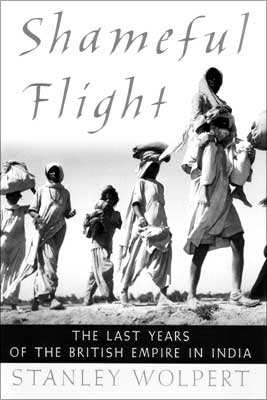

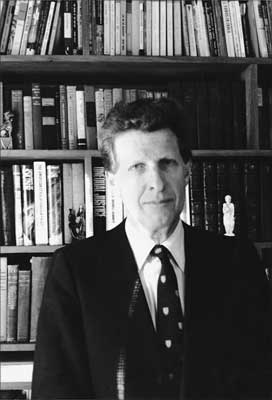

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5"></td></tr></tbody></table>Historian Stanley Wolpert's new book -- Shameful Flight -- revisits Partition, and lays the blame for one of the most horrific episodes of the 20th century squarely on the shoulders of a Briton, finds Arthur J Pais.

Admiral Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas 'Dickie' Mountbatten, the favourite cousin of British King George VI, was famous for his charm. His sycophants in England called it irresistible.

His admirers in the British government even thought of him as a statesman who could charm discontented nationalist leaders of the British Empire, and tease out of them agreements that seemed impossible for other British diplomats to obtain.

So Mountbatten was sent to a deeply restive, increasingly riotous and ceaselessly rebellious India in March 1947 as Britain's viceroy, to hammer agreements that could allow the British to withdraw from the subcontinent with dignity -- leaving the country unified.

'Mountbatten viewed the prospect of ruling India during the Raj's sunset year as challenging as a hard-fought polo game, as he put it the King -- 'The last Chukka in India -- 12 goals down,' writes historian Stanley Wolpert in his riveting, disturbing and provocative book, Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India. "It was a task for only a person of deep insights into India," says Wolpert -- considered by many to be one of the best historians writing on the subcontinent -- in a telephone interview from Los Angeles. "The mission needed a person of great diplomatic skills and [one] who absolutely lacked arrogance."

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td> <td width="10">

</td> <td width="10">

</td></tr></tbody></table> <table cellspaing="0" border="0" cellpadding="0"> <tbody><tr> <td valign="middle" width="5">

</td> <td valign="top" width="35">

</td> <td valign="top" width="35">

</td> <td align="center" height="5" width="20"> | </td> <td valign="top" width="35">

</td> <td align="right" valign="middle" width="7">

</td> </tr> </tbody></table>

</td> </tr> </tbody></table>

The British wanted to leave India by 1948 but Mountbatten cut the time by half

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> What Wolpert would discover some 55 years after the Partition of India -- and the concomitant fleeing of more than 10 million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs from one side to another -- was so horrifying that the 79-year-old historian might have had a hard time believing it. Mountbatten was not only totally inept at dealing with fractious Indian political parties, Wolpert writes, he hastened the process of Independence. The British government wanted to leave India by 1948 but Mountbatten cut the time by half to mid-August 1947 because he was impatient to get back to England and build his naval career.

Much of it had to do with vindicating his father's reputation.

First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy Prince Louis of Battenberg was forced to resign from the fleet during World War I because of his German origin. The family changed the last name to Mountbatten to avoid further vilification. His then 14-year-old son resolved to join the navy and remain in it until he became First Sea Lord.

"So Mountbatten resolved to make fast work of his India job," Wolpert says. "The British cabinet gave him a longer time, but he never had any intention of using it."

Cloak and dagger

Worse, Mountbatten kept the Partition maps of Punjab and Bengal -- with the Muslim areas of the two provinces going to the newly created Pakistan -- secret, until it was opportune for him to make the announcement.

'Mountbatten had resolved to wait until India's Independence Day festivities were all over,' Wolpert writes, 'the flashbulb photos all shot and transmitted worldwide, Dickie's medal-strewn white uniform viewed with admiration by millions, from Buckingham and Windsor palaces to the White House. What a glorious charade of British imperial largesse and power 'peacefully' transferred.'

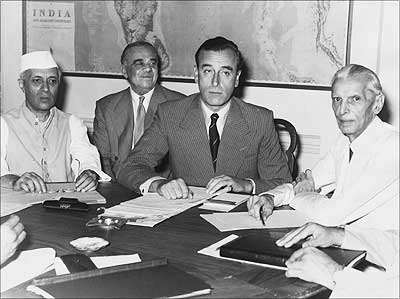

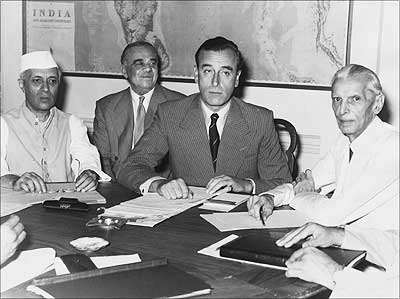

Image: At the conference in New Delhi where Lord Louis Mountbatten disclosed Britain's Partition plan for India. (Left to right) Jawaharlal Nehru, Mountbatten's adviser Lord Ismay, Mountbatten and Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td> <td width="10">

</td> <td width="10">

</td></tr></tbody></table><!--img src="http://im.rediff.com/news/pix/twin.gif" hspace=0 vspace=0 border=0--> Wolpert puts quite a bit of blame for Partition at many Indian leaders, including Nehru

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> In his book published by Oxford University Press -- and which reads in parts like fine detective fiction -- Wolpert has directed quite a bit of blame for Partition at many Indian leaders, including Jawaharlal Nehru, Independent India's first prime minister. One of the reasons for the Labour government in Britain, which had come to power soon after World War II, to grant hasty independence to India was because there was hardly any trust between the Labour and Indian leaders, Wolpert argues.

"There were many Left-leaning Labour leaders who thought their proposals for a gradual transfer of full power to India were not appreciated by Indian leaders," Wolpert says.

"They felt Indian leaders were not being grateful, not appreciating the efforts Labour was putting in to end the colonial rule, unlike the Tories led by (Winston) Churchill."

Many of Wolpert's finger pointing is bound to cause debate and controversy. Already, Professor Ainslee Embree of Columbia University has called the book 'engrossing, but very controversial.'

Dilip Basu, professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, while calling the book 'a delightful read,' added: 'It will be of great interest to anyone curious about whatever happened to the great British Empire and those who often wonder why Indians and Pakistanis endlessly fight with each other.'

Image: Jawaharlal Nehru speaks to Lady Edwina Mountbatten during a display given by the New Delhi Glider Club. On the right, Lady Pamela, daughter of Nehru's guest.

Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td> <td width="10">

</td> <td width="10">

</td></tr></tbody></table> <!--img src="http://im.rediff.com/news/pix/twin.gif" hspace=0 vspace=0 border=0--> 'Mountbatten was the worst viceroy of India, he was the centerpiece of this tragedy'

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> The central villain in the book is undoubtedly the arrogant and unrealistic Mountbatten. "Partition maps revealing the butchered boundary lines drawn by Sir Cyril Radcliffe," Wolpert says, "through the Sikh heartland of Punjab and the east of Calcutta in Bengal, were kept under lock and key on Mountbatten's orders."

Radcliffe, a barrister, had never set foot on Indian soil before 1947. "He was to accomplish, in a month, work that should have taken at least a year," Wolpert points out. "He was so afraid of what he had done -- worried that Sikhs, Hindus or Muslims would kill him -- (that) he left India hastily."

Wolpert says had the governors of Punjab and Bengal known about the way the two provinces were being partitioned, "they could have, with their early knowledge, saved countless lives by dispatching troops and trains to what would soon become the lines of fire and blood.

"The rapid departure of the British from the region was the catalyst for over half a century of violence, a legacy that lives on today," the historian says, discussing why Partition still holds interest for him.

"The Indian leaders as well as their counterparts in England failed to appreciate how bad and how weak a viceroy Mountbatten was," Wolpert continues. "In many ways, he was the worst viceroy of India, he was the centerpiece of this tragedy."

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td> <td width="10">

</td> <td width="10">

</td></tr></tbody></table> <!--img src="http://im.rediff.com/news/pix/twin.gif" hspace=0 vspace=0 border=0--> Churchill called the time limit a 'guillotine'

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Shameful flight The failure of the British government to see the larger picture and Mountbatten's preoccupation with his career created explosive conditions made worse by the warring Indian leaders, he says.

"I still wonder how it was possible for the leaders of Great Britain, barely two years after defeating, with American support, the armies of Hitler and Mussolini, to withdraw 14,000 British officers in such unseemly haste from India," he adds.

Churchill, who was bitterly opposed to an independent India, cautioned against the sudden departure. He thought the original 14-month schedule was too hasty. His opposition 'could be counted as one of history's supremely ironic moments,' writes Wolpert.

'How can one suppose that the thousand year-gulf that yawns between Muslim and Hindu would be bridged in 14 months?' Churchill asked. He called the time limit a 'guillotine,' adding that the hasty exit could bring a terrible name to Britain. The 'shameful flight' could result in chaos and carnage. 'Would it not be a world crime,' he asked, 'that would stain our good name for ever?'

He warned it would be a 'shameful flight, by a premature hurried scuttle.'

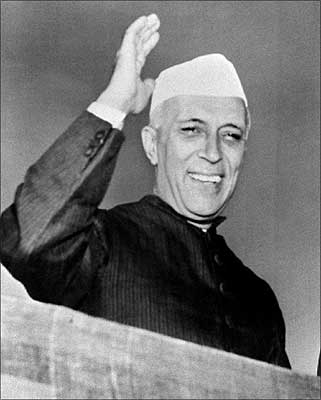

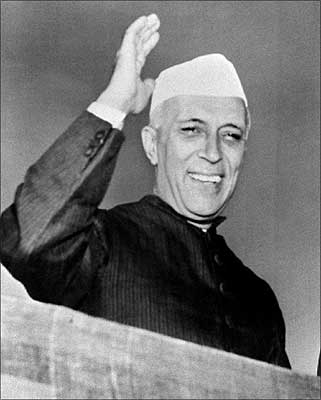

Image: Washington, DC. October 13, 1949: Jawaharlal Nehru arrives in the US.

Photograph: Staff/AFP/Getty Images

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td>

</td></tr> <tr> </tr><tr> <td valign="top">

</td> <td width="10">

</td> <td width="10">

</td></tr></tbody></table> <!--img src="http://im.rediff.com/news/pix/twin.gif" hspace=0 vspace=0 border=0--> Wolpert sees parallels between the aftermath of 9/11 and what happened in India in 1947

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Even the eventual founder of Pakistan Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who would not give up his demand for an independent Muslim State, was worried over the way the Partition was being rushed. Wolpert, professor of history emeritus at the University of California, Los Angeles, dedicates his newest book 'To the memory of the millions of defenseless Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh victims of the British India's Partition.'

"For half a decade, I have pondered the question of the tragedy of Partition, and I have dealt with it in some form or the other in many of my books," Wolpert says. "I have also been trying to understand the role of the major people involved in Partition."

Wolpert had been thinking of a book exclusively focusing on Partition for many years but, but because of his other assignments, could begin working on it only about six years ago.

"I am glad I waited for," he said from his Los Angeles home on a Sunday afternoon. "After half a century of studying and teaching Indian history and writing 20 books on the subcontinent, I finally got an opportunity to reflect on one of the most momentous events in history."

He sees parallels between the aftermath of 9/11 and what happened in India in 1947. He sees the "same kind of madness, the same kind of arrogance (as in Mountbatten's decisions) in going to war against Iraq."

Petty politics

The infighting between the Indian leaders added to the tension and problems.

Some of them changed their minds too quickly. Jinnah, who complained the British were prepared to give him only a moth-eaten Pakistan -- meaning a country with the partitioned states of Punjab and Bengal -- at one point suddenly told the British he was not averse to the idea of an independent Bengal ruled by a fellow Muslim League leader.

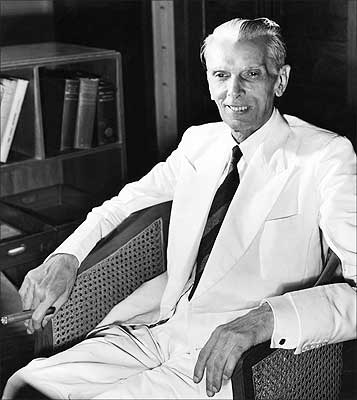

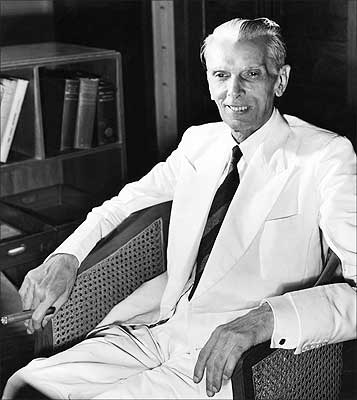

Image: Karachi, Pakistan. September 18, 1947: Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan during an interview.

Photograph: Bert Brandt/AFP/Getty Images

Gandhi sent word to Jinnah that he would not object to Jinnah being the leader of free India instead of Nehru

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Nehru gets a lot of blame for going with Mountbatten's desire for not just partitioning the country hastily but also for agreeing to divide Punjab and Bengal. Gandhi had refused for seven years, since Jinnah proposed a separate Muslim nation, to support a 'vivisection of the Mother,' arguing 'Muslims can never cut themselves away from their Hindu or Christian brethren. We are all children of the same Mother.'

He was so serious about saving India that he sent word, a few months before Partition, to Jinnah through Mountbatten that he would not object to Jinnah being the leader of free and united India instead of Nehru. But Jinnah -- who always mistrusted the Mahatma, calling him 'wily Gandhi' -- had no use for such overtures.

Nehru is also faulted for not listening to Gandhi in getting Jinnah to mediate in the escalating violence in undivided Kashmir. Gandhi even wondered if holding a plebiscite in Kashmir could end the looming violence there.

Why did Nehru listen so much to Mountbatten?

Image: Lord Mountbatten preparing on the final stages of India's Partition.

Photograph: Rediff Archives'

Those who forget history...

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Nehru had talked about Mountbatten's fatal charm," Wolpert says. "Of course, he was flattering Mountbatten when he said that. But Nehru unfortunately came too much under the influence of Mountbatten, exacerbated by Nehru's education in England. Nehru was charmed by the English upper world, he thought he could trust and work with Mountbatten. "Mountbatten's royal blood appealed as much to the rulers of princely states in India," Wolpert continues, "as his radical views and social charms did to Nehru. His charm was so much Nehru was blinded by it."

Asked if Nehru's relationship with Mountbatten's wife Edwina played a role, the historian says, "It helped him cloud the danger of what Mountbatten was doing."

Wolpert doesn't fight the idea that Partition looked inevitable by 1947, and he understands why Nehru, seeing the way Hindus had been killed in Bengal and Punjab, agreed to the partition of the two provinces.

"But the real solution to any massacre is not to make more violence by drawing a line blindly through a province," the historian points out.

Image: Lord Mountbatten, Jawaharlal Nehru and Lady Mountbatten share a light moment preparing for the final stages of freedom for India.

Years later, Mountbatten would whisper now and then how he had botched up the Independence process

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Years after Partition, Mountbatten would whisper now and then how he had botched up the Independence process. Nehru 'finally awakened,' and admitted in a letter to the Nawab of Bhopal, a friend, 'Partition came and we accepted it because we thought that perhaps that way, however painful it was, we might have some peace.

'And yet, the consequences of that Partition have been so terrible that one is inclined to think that anything else would have been preferable,' Nehru added.

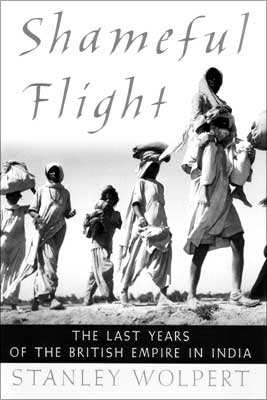

At the end of his six-year research and writing, Wolpert was looking for a picture for the book's dust jacket. He had gone through hundreds of pictures of Partition. And he had also seen pictures offering glimpses of thousands of people who perished in the tragedy -- some estimates believe over a million were killed.

"Suddenly, I came across an image that encapsulated the tragedy," he says. It is a picture by the well-known photographer Margaret Bourke-White, showing mostly bare-footed refugees going to places they felt would be safe from the communal carnage.

The image of a Sikh man in the same photograph carrying a woman on his shoulders also spoke volumes, Wolpert says. "The picture brought to our attention the fact that these poor, barefoot people with no possessions had to make the perilous journey because of the idiocy and arrogance of those who had a duty to protect them."

Image: Partition woes: People on their way to India leaving behind their homes and land in Pakistan.

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5"></td></tr></tbody></table>Historian Stanley Wolpert's new book -- Shameful Flight -- revisits Partition, and lays the blame for one of the most horrific episodes of the 20th century squarely on the shoulders of a Briton, finds Arthur J Pais.

Admiral Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas 'Dickie' Mountbatten, the favourite cousin of British King George VI, was famous for his charm. His sycophants in England called it irresistible.

His admirers in the British government even thought of him as a statesman who could charm discontented nationalist leaders of the British Empire, and tease out of them agreements that seemed impossible for other British diplomats to obtain.

So Mountbatten was sent to a deeply restive, increasingly riotous and ceaselessly rebellious India in March 1947 as Britain's viceroy, to hammer agreements that could allow the British to withdraw from the subcontinent with dignity -- leaving the country unified.

'Mountbatten viewed the prospect of ruling India during the Raj's sunset year as challenging as a hard-fought polo game, as he put it the King -- 'The last Chukka in India -- 12 goals down,' writes historian Stanley Wolpert in his riveting, disturbing and provocative book, Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India. "It was a task for only a person of deep insights into India," says Wolpert -- considered by many to be one of the best historians writing on the subcontinent -- in a telephone interview from Los Angeles. "The mission needed a person of great diplomatic skills and [one] who absolutely lacked arrogance."

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td></tr></tbody></table> <table cellspaing="0" border="0" cellpadding="0"> <tbody><tr> <td valign="middle" width="5">

</td> <td align="center" height="5" width="20"> | </td> <td valign="top" width="35">

</td> <td align="right" valign="middle" width="7">

The British wanted to leave India by 1948 but Mountbatten cut the time by half

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> What Wolpert would discover some 55 years after the Partition of India -- and the concomitant fleeing of more than 10 million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs from one side to another -- was so horrifying that the 79-year-old historian might have had a hard time believing it. Mountbatten was not only totally inept at dealing with fractious Indian political parties, Wolpert writes, he hastened the process of Independence. The British government wanted to leave India by 1948 but Mountbatten cut the time by half to mid-August 1947 because he was impatient to get back to England and build his naval career.

Much of it had to do with vindicating his father's reputation.

First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy Prince Louis of Battenberg was forced to resign from the fleet during World War I because of his German origin. The family changed the last name to Mountbatten to avoid further vilification. His then 14-year-old son resolved to join the navy and remain in it until he became First Sea Lord.

"So Mountbatten resolved to make fast work of his India job," Wolpert says. "The British cabinet gave him a longer time, but he never had any intention of using it."

Cloak and dagger

Worse, Mountbatten kept the Partition maps of Punjab and Bengal -- with the Muslim areas of the two provinces going to the newly created Pakistan -- secret, until it was opportune for him to make the announcement.

'Mountbatten had resolved to wait until India's Independence Day festivities were all over,' Wolpert writes, 'the flashbulb photos all shot and transmitted worldwide, Dickie's medal-strewn white uniform viewed with admiration by millions, from Buckingham and Windsor palaces to the White House. What a glorious charade of British imperial largesse and power 'peacefully' transferred.'

Image: At the conference in New Delhi where Lord Louis Mountbatten disclosed Britain's Partition plan for India. (Left to right) Jawaharlal Nehru, Mountbatten's adviser Lord Ismay, Mountbatten and Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td></tr></tbody></table><!--img src="http://im.rediff.com/news/pix/twin.gif" hspace=0 vspace=0 border=0--> Wolpert puts quite a bit of blame for Partition at many Indian leaders, including Nehru

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> In his book published by Oxford University Press -- and which reads in parts like fine detective fiction -- Wolpert has directed quite a bit of blame for Partition at many Indian leaders, including Jawaharlal Nehru, Independent India's first prime minister. One of the reasons for the Labour government in Britain, which had come to power soon after World War II, to grant hasty independence to India was because there was hardly any trust between the Labour and Indian leaders, Wolpert argues.

"There were many Left-leaning Labour leaders who thought their proposals for a gradual transfer of full power to India were not appreciated by Indian leaders," Wolpert says.

"They felt Indian leaders were not being grateful, not appreciating the efforts Labour was putting in to end the colonial rule, unlike the Tories led by (Winston) Churchill."

Many of Wolpert's finger pointing is bound to cause debate and controversy. Already, Professor Ainslee Embree of Columbia University has called the book 'engrossing, but very controversial.'

Dilip Basu, professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, while calling the book 'a delightful read,' added: 'It will be of great interest to anyone curious about whatever happened to the great British Empire and those who often wonder why Indians and Pakistanis endlessly fight with each other.'

Image: Jawaharlal Nehru speaks to Lady Edwina Mountbatten during a display given by the New Delhi Glider Club. On the right, Lady Pamela, daughter of Nehru's guest.

Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td></tr></tbody></table> <!--img src="http://im.rediff.com/news/pix/twin.gif" hspace=0 vspace=0 border=0--> 'Mountbatten was the worst viceroy of India, he was the centerpiece of this tragedy'

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> The central villain in the book is undoubtedly the arrogant and unrealistic Mountbatten. "Partition maps revealing the butchered boundary lines drawn by Sir Cyril Radcliffe," Wolpert says, "through the Sikh heartland of Punjab and the east of Calcutta in Bengal, were kept under lock and key on Mountbatten's orders."

Radcliffe, a barrister, had never set foot on Indian soil before 1947. "He was to accomplish, in a month, work that should have taken at least a year," Wolpert points out. "He was so afraid of what he had done -- worried that Sikhs, Hindus or Muslims would kill him -- (that) he left India hastily."

Wolpert says had the governors of Punjab and Bengal known about the way the two provinces were being partitioned, "they could have, with their early knowledge, saved countless lives by dispatching troops and trains to what would soon become the lines of fire and blood.

"The rapid departure of the British from the region was the catalyst for over half a century of violence, a legacy that lives on today," the historian says, discussing why Partition still holds interest for him.

"The Indian leaders as well as their counterparts in England failed to appreciate how bad and how weak a viceroy Mountbatten was," Wolpert continues. "In many ways, he was the worst viceroy of India, he was the centerpiece of this tragedy."

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td valign="top">

</td></tr></tbody></table> <!--img src="http://im.rediff.com/news/pix/twin.gif" hspace=0 vspace=0 border=0--> Churchill called the time limit a 'guillotine'

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Shameful flight The failure of the British government to see the larger picture and Mountbatten's preoccupation with his career created explosive conditions made worse by the warring Indian leaders, he says.

"I still wonder how it was possible for the leaders of Great Britain, barely two years after defeating, with American support, the armies of Hitler and Mussolini, to withdraw 14,000 British officers in such unseemly haste from India," he adds.

Churchill, who was bitterly opposed to an independent India, cautioned against the sudden departure. He thought the original 14-month schedule was too hasty. His opposition 'could be counted as one of history's supremely ironic moments,' writes Wolpert.

'How can one suppose that the thousand year-gulf that yawns between Muslim and Hindu would be bridged in 14 months?' Churchill asked. He called the time limit a 'guillotine,' adding that the hasty exit could bring a terrible name to Britain. The 'shameful flight' could result in chaos and carnage. 'Would it not be a world crime,' he asked, 'that would stain our good name for ever?'

He warned it would be a 'shameful flight, by a premature hurried scuttle.'

Image: Washington, DC. October 13, 1949: Jawaharlal Nehru arrives in the US.

Photograph: Staff/AFP/Getty Images

<table align="left" border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0"><tbody><tr><td>

</td></tr> <tr> </tr><tr> <td valign="top">

</td></tr></tbody></table> <!--img src="http://im.rediff.com/news/pix/twin.gif" hspace=0 vspace=0 border=0--> Wolpert sees parallels between the aftermath of 9/11 and what happened in India in 1947

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Even the eventual founder of Pakistan Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who would not give up his demand for an independent Muslim State, was worried over the way the Partition was being rushed. Wolpert, professor of history emeritus at the University of California, Los Angeles, dedicates his newest book 'To the memory of the millions of defenseless Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh victims of the British India's Partition.'

"For half a decade, I have pondered the question of the tragedy of Partition, and I have dealt with it in some form or the other in many of my books," Wolpert says. "I have also been trying to understand the role of the major people involved in Partition."

Wolpert had been thinking of a book exclusively focusing on Partition for many years but, but because of his other assignments, could begin working on it only about six years ago.

"I am glad I waited for," he said from his Los Angeles home on a Sunday afternoon. "After half a century of studying and teaching Indian history and writing 20 books on the subcontinent, I finally got an opportunity to reflect on one of the most momentous events in history."

He sees parallels between the aftermath of 9/11 and what happened in India in 1947. He sees the "same kind of madness, the same kind of arrogance (as in Mountbatten's decisions) in going to war against Iraq."

Petty politics

The infighting between the Indian leaders added to the tension and problems.

Some of them changed their minds too quickly. Jinnah, who complained the British were prepared to give him only a moth-eaten Pakistan -- meaning a country with the partitioned states of Punjab and Bengal -- at one point suddenly told the British he was not averse to the idea of an independent Bengal ruled by a fellow Muslim League leader.

Image: Karachi, Pakistan. September 18, 1947: Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan during an interview.

Photograph: Bert Brandt/AFP/Getty Images

Gandhi sent word to Jinnah that he would not object to Jinnah being the leader of free India instead of Nehru

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Nehru gets a lot of blame for going with Mountbatten's desire for not just partitioning the country hastily but also for agreeing to divide Punjab and Bengal. Gandhi had refused for seven years, since Jinnah proposed a separate Muslim nation, to support a 'vivisection of the Mother,' arguing 'Muslims can never cut themselves away from their Hindu or Christian brethren. We are all children of the same Mother.'

He was so serious about saving India that he sent word, a few months before Partition, to Jinnah through Mountbatten that he would not object to Jinnah being the leader of free and united India instead of Nehru. But Jinnah -- who always mistrusted the Mahatma, calling him 'wily Gandhi' -- had no use for such overtures.

Nehru is also faulted for not listening to Gandhi in getting Jinnah to mediate in the escalating violence in undivided Kashmir. Gandhi even wondered if holding a plebiscite in Kashmir could end the looming violence there.

Why did Nehru listen so much to Mountbatten?

Image: Lord Mountbatten preparing on the final stages of India's Partition.

Photograph: Rediff Archives'

Those who forget history...

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Nehru had talked about Mountbatten's fatal charm," Wolpert says. "Of course, he was flattering Mountbatten when he said that. But Nehru unfortunately came too much under the influence of Mountbatten, exacerbated by Nehru's education in England. Nehru was charmed by the English upper world, he thought he could trust and work with Mountbatten. "Mountbatten's royal blood appealed as much to the rulers of princely states in India," Wolpert continues, "as his radical views and social charms did to Nehru. His charm was so much Nehru was blinded by it."

Asked if Nehru's relationship with Mountbatten's wife Edwina played a role, the historian says, "It helped him cloud the danger of what Mountbatten was doing."

Wolpert doesn't fight the idea that Partition looked inevitable by 1947, and he understands why Nehru, seeing the way Hindus had been killed in Bengal and Punjab, agreed to the partition of the two provinces.

"But the real solution to any massacre is not to make more violence by drawing a line blindly through a province," the historian points out.

Image: Lord Mountbatten, Jawaharlal Nehru and Lady Mountbatten share a light moment preparing for the final stages of freedom for India.

Years later, Mountbatten would whisper now and then how he had botched up the Independence process

November 29, 2006

<table border="0" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" height="5"><tbody><tr><td height="5">

</td></tr></tbody></table> Years after Partition, Mountbatten would whisper now and then how he had botched up the Independence process. Nehru 'finally awakened,' and admitted in a letter to the Nawab of Bhopal, a friend, 'Partition came and we accepted it because we thought that perhaps that way, however painful it was, we might have some peace.

'And yet, the consequences of that Partition have been so terrible that one is inclined to think that anything else would have been preferable,' Nehru added.

At the end of his six-year research and writing, Wolpert was looking for a picture for the book's dust jacket. He had gone through hundreds of pictures of Partition. And he had also seen pictures offering glimpses of thousands of people who perished in the tragedy -- some estimates believe over a million were killed.

"Suddenly, I came across an image that encapsulated the tragedy," he says. It is a picture by the well-known photographer Margaret Bourke-White, showing mostly bare-footed refugees going to places they felt would be safe from the communal carnage.

The image of a Sikh man in the same photograph carrying a woman on his shoulders also spoke volumes, Wolpert says. "The picture brought to our attention the fact that these poor, barefoot people with no possessions had to make the perilous journey because of the idiocy and arrogance of those who had a duty to protect them."

Image: Partition woes: People on their way to India leaving behind their homes and land in Pakistan.

jee te karda hai saalyaan nu maar deyaan bt o te pehlaan hi bhajj challe oopar. :t :t

jee te karda hai saalyaan nu maar deyaan bt o te pehlaan hi bhajj challe oopar. :t :t